Red Eye Interview

Rooted Futures: An interview with Zena Holloway on the Art of Living Materials

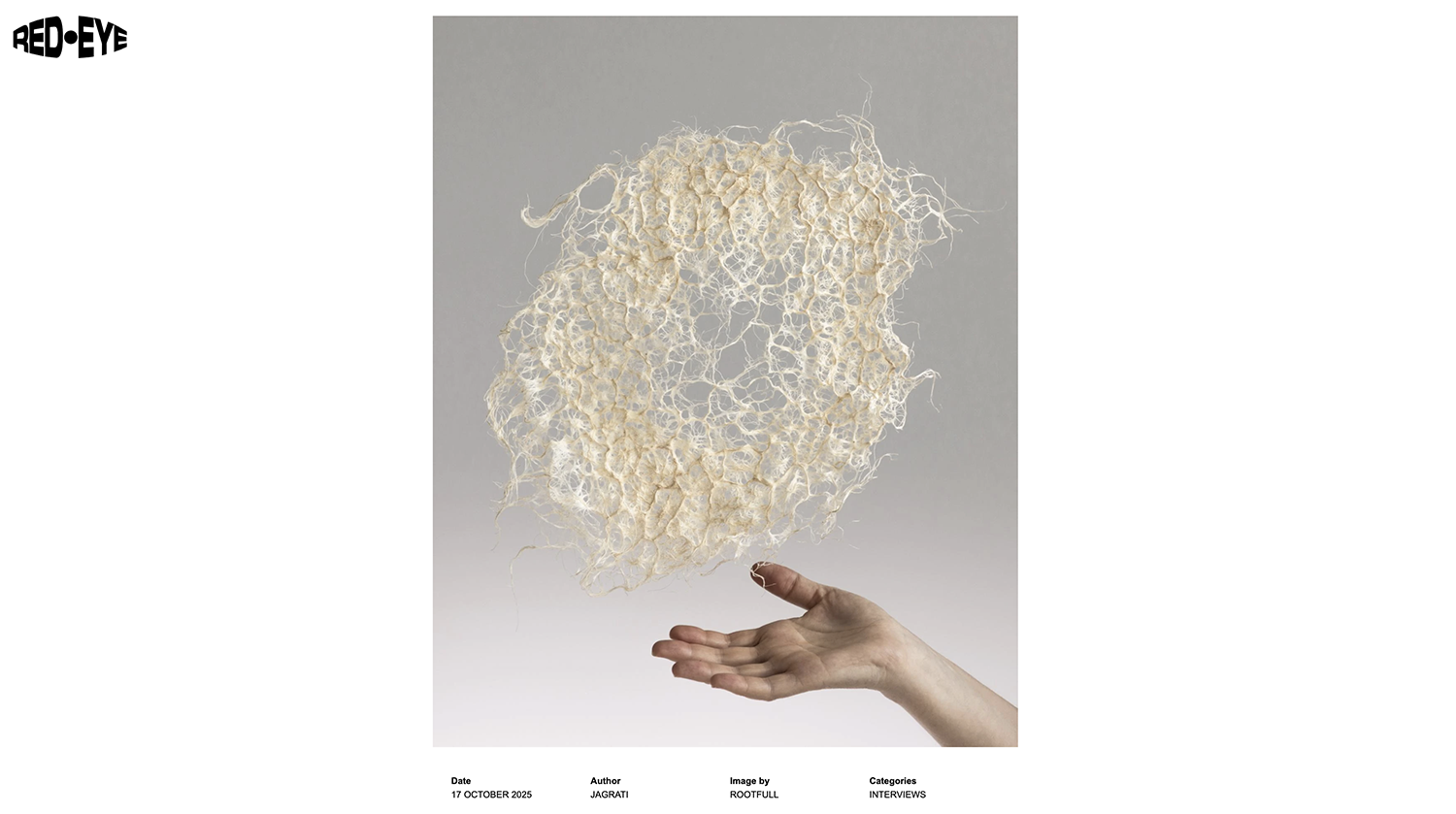

Zena Holloway, once renowned for her ability to capture the hushed poetry of underwater realms, has transformed her creative compass toward something even more elemental: the living material beneath our feet. With her current project, Rootfull, Holloway moves beyond the lens and into the soil, cultivating biodegradable forms, sculptures, textiles, and vessels grown entirely from plant roots.

In an age where the consequences of overproduction and synthetic permanence are impossible to ignore, Holloway offers a radically gentle proposal: what if design could grow, age, and die like a living thing? What if it listened to its environment instead of imposing upon it? Her work isn’t just an artistic experiment; it’s a form of quiet rebellion against the extractive logic that defines so much of our material culture.

Rootfull is a living archive of her discoveries. A soft, fibrous manifesto. A vision of objects not built but nurtured. And behind it all is a self-taught innovator who trusts the wisdom of nature more than the noise of industry.

“I was diving and seeing our planet from underwater for a very long time,” Holloway says, recalling her decades as a photographer exploring marine ecosystems. “You'd start to notice the plastic bags floating like jellyfish, old car tyres lying ghost-like on the seabed—this material problem became impossible to ignore.”

By 2018, the enchantment she once felt, capturing the ocean’s sublime textures, had begun to erode under the weight of these reminders. “The camera could no longer hold what I needed to say,” she explains. “Biology became the perfect narrative. It had everything I wanted to express.”

What inspired your shift from photography to living materials?

It was gradual. I spent years trying to show the fragility and beauty of the sea, but the pollution kept creeping into my images. It changed what I wanted to do. I wanted to make something that could disappear, something that wouldn’t leave a trace. That led me to biology, and eventually, to roots.

Why work with roots instead of continuing with mycelium?

Roots are flexible, resilient, and more forgiving. They’re easier to manipulate, and the forms they take can be remarkably beautiful. Mycelium is amazing, but roots gave me more room to play.

Holloway’s journey has never followed traditional academic routes. Having left formal education at eighteen, she taught herself through experimentation, failure, and a deep commitment to research. She found unexpected kinship in visionary projects like Carole Collet’s Biolace, which imagined genetically modified plants that could produce food above ground and fibre below. “I loved the idea of dual-purpose systems,” she says. “It was hopeful.”

Rootfull uses simple principles; roots are guided to grow into moulds or frames, forming everything from garments and vessels to light fixtures. Once the object has served its purpose, it can be returned to the earth, decomposing without harm. This is not just sustainability, it is a reorientation of value, a celebration of the temporary.

What do you make of the word ‘sustainability’?

It’s lost meaning. It’s been watered down. What I care about is regeneration. Composting. Circularity that isn’t a trend but a default. We need materials that give back more than they take. Rootfull tries to do that.

Though Holloway hasn’t conducted a formal life-cycle assessment of her root-grown materials, she knows the act of growing sequesters carbon. “I think that’s reason enough to continue,” she says. “Every object is a little experiment. A question posed to the soil.”

The term compostable bothers her—too vague, too greenwashed. But the essence behind it still matters. Her pieces are carbon-negative by nature, their decay part of the beauty. “To let something go is part of the process,” she adds.

“If we let go of control a bit and let biology lead, we might end up somewhere more beautiful than we imagined.”

Do you think of yourself more as an artist or a scientist?

A: Honestly, I’m just curious. Sometimes the idea comes first, sometimes the roots dictate the form. I might imagine a garment and then realise I need to learn basket weaving. I follow what the roots are telling me. Listening is everything.

Her workspace resembles a hybrid greenhouse and sculpture lab, stacked with frames, mesh moulds, trays of seedlings, drying roots, and sketches. It’s tactile and slow. On one day, she might be crafting an intricate lace-like lampshade; on another, working with a fashion house to prototype root-grown corsets. Her work has appeared in galleries and design fairs, though commercialising the material remains complex.

Still, Holloway isn’t interested in holding the knowledge too tightly.

What’s next for Rootfull?

Collaboration. This can’t be mine alone. The more people experiment with it, the stronger the material becomes. I’m working on a system where some processes are open-source, others are protected for quality. But the idea is to let Rootfull grow in directions I can’t predict.

What do you hope people feel when they see your work?

Just one thing—that nature is brilliant. If we work with it instead of against it, we might still find our way back. There’s still time to create differently.